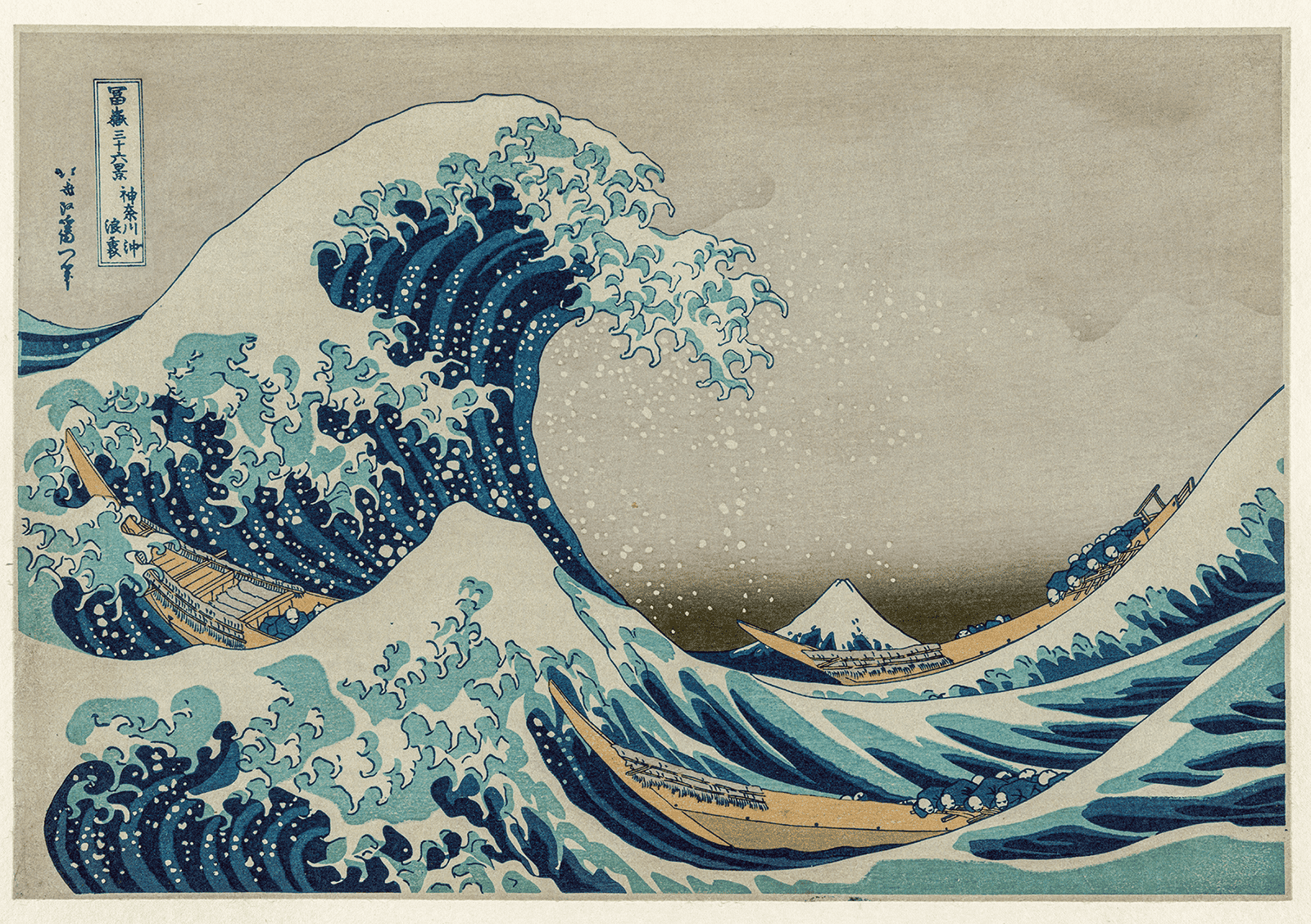

In Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa, it’s difficult not to notice the wave. It dominates the frame, it commands attention. But look closely, almost quietly placed within the frame, and in the distance you’ll see Mount Fuji, present the entire time, yet commonly missed.

In care, behaviour is often the wave.

It is immediate, urgent. It breaks routines and demands a response. The raised voice, the refusal, the self-harm, the aggression, the sudden withdrawal. That is what incident reports record, what colleagues talk about in handovers. It is what systems are designed to respond to.

But behaviour is rarely the whole picture.

Behind it, sometimes long before, are factors less visible: trauma histories, anxiety, sensory overwhelm, fear of loss of control, communication barriers, previous negative experiences with authority. These are the mountains in the distance.

The quality of care often depends on whether staff in care are trained to notice both.

When We Look, But Don’t See

It’s no secret that teams operate under significant pressure. Risk must be managed and safety must be maintained. In these conditions, it is entirely human to respond to what is in front of you.

Escalating behaviour becomes the problem to solve.

But if the only lens through which behaviour is viewed is to contain or intervene, we risk responding to symptoms without understanding their origin. Over time, this can create a cycle in which incidents are managed competently yet continue to reoccur because the underlying drivers remain unaddressed.

Trauma-informed practice invites a slightly different orientation. It broadens the frame. It asks not only, “How do we bring this situation under control?” but also, “What might have contributed to this?”

When staff are supported to recognise the early stages of escalation, interventions can begin sooner. De-escalation becomes preventative rather than reactive. The wave may still rise, but it is less likely to crash with the same force.

Clarity reduces intensity.

Hearing, But Not Listening

There is another layer to this: how expectation shapes interaction. The Influence of Assumptions

In care, it is possible to hear a person without truly listening, to observe behaviour without understanding context. To label someone as “non-compliant”, or “attention-seeking” without asking what experience sits underneath those words.

Language plays a role here. The terms we use can narrow our perception. Once a person is described primarily by their most visible behaviour, it becomes harder to see anything else.

If a person is introduced as “high-risk” or “aggressive”, that description, even when well-intended, can influence how the next professional approaches them. Shoulders tighten, tone becomes more guarded, vigilance increases. The interaction starts with a degree of distance.

It is not conscious prejudice. We prepare for what we anticipate.

But individuals can be acutely sensitive to how they are approached. Anxiety can be mirrored. Tension can be felt. In environments where many people have experienced trauma, powerlessness, or misunderstanding, those small signals can matter.

This is why language and perception are not abstract concerns, they shape practice. When behaviour is framed as a problem to be controlled, responses tend to centre on containment. When behaviour is understood as communication, responses can become more emphatic, and ultimately more effective.

Seeing Differently Changes Outcomes

Significant attention is given to physical intervention training, and rightly so. Staff must know how to respond safely when situations become high risk. But prevention sits upstream.

Effective positive behaviour management is not built solely on techniques. It is built on perception. The ability to notice patterns and connect behaviour with context. To understand that the visible “wave” is often the final stage of a much longer process.

When teams develop shared understanding around:

- The stages of escalation

- Early intervention strategies

- Non-restrictive de-escalation techniques

- Post-crisis debriefing as a learning opportunity

they are not just improving compliance, but building environments where crises are shorter, less frequent, and less intense.

Seeing the mountain does not remove the wave. But it changes how we prepare for it.

A Discipline, Not an Instinct

Looking beyond behaviour is not something that happens automatically. Under stress, humans revert to speed, control, and certainty. Trauma-informed approaches require something more deliberate. Reflective practice, ethical awareness, and ongoing skill development.

Hokusai’s wave has not changed in 200 years. But most people still overlook Mount Fuji.

In care, the visible crisis will always demand attention, that’s the nature of frontline work. But the quality of care often hinges on what we notice beyond it. To pause and ask what else is present.

When professionals are supported to look again, listen more carefully, and question assumptions, practice shifts.And sometimes, the mountain becomes visible before the wave ever rises.